December 2023

Dr. Fall, could you tell us about your background?

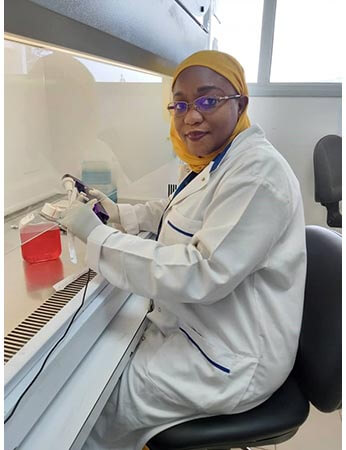

I am currently a research associate at the Institut Pasteur de Dakar (IPD) in Senegal, where my research focuses on arboviruses and viral hemorrhagic fevers in support of the public health sector. I also act as Deputy Head of the WHO Collaborating Centre for Arboviruses and Hemorrhagic Fevers and Head of the WHO Regional Reference Laboratory for Yellow Fever. I am engaged in several national and international programs, including PICREID (NIH funds), HEVA (Gates Foundation funds), TWAS-saliva (a UNESCO program led by Women in Science for the Developing World (OSDW)), YEFE (Wellcome Trust funds), and NIFTY (EDCTP funds).

Within the frame of these projects, I am studying the viral detection and characterization in humans and arthropods, the seroprevalence of hepatitis E in patients with acute jaundice recruited for yellow fever surveillance in Africa, and the non-inferiority in terms of seroconversion of fractionated doses of yellow fever vaccine compared to the full dose in a context of supply shortage. I also train and supervise master’s and PhD students at Senegalese Universities and organize training workshops for the World Organization (WHO) and the West Africa Health Organization (WAHO). Academically, I have a PhD in Biology-Health from the University of Montpellier-II in 2009.

What is your current research focus?

My research focuses on vector-virus-host interactions, in particular on the transmission of arboviruses (mainly West Nile, Koutango, Usutu, and Rift Valley fever viruses) by mosquito vectors, their pathogenesis in vertebrate hosts using a mouse model, and the impact of factors such as viral genetic diversity, mosquito saliva and RNA interference on arbovirus transmission and infection outcome in vertebrates.

Where would you like to take your research in the future?

I’d particularly like to carry out more sophisticated, mechanistic research using genomics, proteomics, reverse genetics (infectious clones, pseudoviruses), and different animal models (humanized mice, hamsters, etc.) to develop strategies and tools to assess the risk of emerging arboviruses and to better respond to and control likely future epidemics. I’d also like to build capacity in Senegal, by developing research into emerging pathogens, and training students in the relevant disciplines.

What are some of the hurdles you face to getting there?

The main challenges I’ve faced are the lack of funding and specific platforms or animal models at a local level (proteomics, reverse genetics, humanized animal models, etc). Yet establishing collaborations with institutions that possess these ingredients, and building local capacity are sure to enhance our research ecosystem.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, such a collaboration has been made with partners in South Africa on the production of Sars-CoV2 pseudo-virus that will be used for serological assays. This technology could be later used for other viruses including arboviruses.

We have a long way to go before reaching parity in the number of female vs male investigators in your field. Do you ever feel like the “poster woman” for African women scientists?

When I received a grant from the Organization of Women Scientists in Developing Countries and learned that my project was among the top 20 out of 200 evaluated, I felt like a “poster woman” in Sub-Saharan Africa. What’s more, given my monitoring and training responsibilities, many people I talk to, especially in some other African countries, assume before meeting me that I’m a man because, in their opinion, a woman can’t carry out all these activities. This gives me more courage and confidence to carry on. I think I still have a long way to go in the research field before becoming a real “poster woman” for African women scientists.

What would you say to young girls around the world who are curious about becoming scientists?

Being a woman in science means, first and foremost, having precise goals and a passion for the field because it requires lots of sacrifice but can be very rewarding. For me, knowing that I’m contributing to research and public health efforts on infectious diseases in my country and some other African countries gives me great pride and personal satisfaction. I’d tell them to be courageous, perseverant, and motivated because being a woman scientist is difficult but not impossible.

Sciences are broad, but when it comes to my field, “Public Health and Research into Emerging pathogens”, it’s a rewarding one as you can actually see the tangible results of your research through publications, and participation in meetings, etc. Knowing that you’re making all these efforts to support both people and your country in detecting epidemics at an early stage, and providing responses to prevent their spread, is truly gratifying and fulfilling.

When you’re not working, what do you enjoy doing?

I like watching action movies and football matches. Babysitting is always one of my favorite things.